Anna Lawrence grew up in Halesowen on the outskirts of the Black Country, a few feet from where her ancestors forged nails in their back yard. She studied English at the University of Oxford and Children’s Literature at the University of Warwick. Before becoming a lecturer in creative writing at Birmingham City University, Anna was, among other things, a trainee prison governor, and this fuelled her interest in how places shape the experience of people living there. She explored the interaction of the magical and the mundane in her novel Ruby’s Spoon (Chatto & Windus, 2010), set in a fictional Black Country town where witches and mermaids may (or may not) reside, and her poetry investigates similar territory.

Deep England/ England’s Deeps: a response to Anna Lawrence’s ‘Quarry’

‘Her memories slip like grit under her feet’.

A sister remembers the loving violence of her childhood relationship with her brother, looking backwards to a past that is fading into history. Back then, new infrastructure was reshaping familiar landscapes. Those growing up at the time felt the pressure of change, fear of the unknown speed of things, even in that middle space of England between country and city; a place where – as Denis Cosgrove writes – the seeming balance of pastoral is always overshadowed by the intimation of death.[1]

She tries to go back from her modern urban life to the place of her dreams and fears. She wants to commemorate that love of brother and sister, now so clearly gone. But even when she finds the place itself, it is no longer that place. The cycles of progress have swept it clean, drained it of meaning for her, in the paradox of feeling for place in an age of improvement and reclamation.

This is Anna Lawrence’s short story ‘Quarry’. But that rough outline resonates with George Eliot’s work – and in particular, The Mill on the Floss(1860) and Silas Marner (1861). Lawrence is writer in residence on the AHRC funded project Provincialism: Literature and the Cultural Politics of Middleness in Britainand has been commissioned to produce work in response to Eliot’s bicentenary in 2019. ‘Quarry’ is the first story to result from that and one which – as its polyvalent title suggests – figures writing and memory as pursuit; as elusive prey; as excavation and sudden plunge; as careful, patient scraping away at recalcitrant material.

‘Quarry’ explores a sister’s memories of her older brother in a childhood threatened by small violences, passionate love and a great chasm of absence. We know the fates of these two – the bookish girl, Bub, and Gav with his bikes and torn jeans – will take them different places, carried on the currents of social (im)mobilities in the late twentieth century. The relationship echoes the violence and love of Tom and Maggie Tulliver, thrust apart by forces of change, lives ended by environmental disaster, and the troubled nostalgia of Eliot’s Brother and Sister Sonnets. The quarry that is so full of fears for young Bub haunts those poems too, as it does Silas Marner, where Dunsey Cass ‘stepped forward into darkness’ by its slippery edge. The pit outside Silas Marner’s house is drained thanks to progress in landscape management; but whilst the quarry reveals his stolen money and a long-sunk family secret, his attempts to find the truth of his own past back in Lantern Yard are fruitless. The restless energies of capitalism mean that the place he remembers has gone. Nothing remains apart from his memory and the trauma of his shunning.

Silas finds that ‘The old place is all swep’ away’ for a new factory in his former home in the industrial North; Bub finds ‘rewilding’, conservation projects, newts and rangers at the old quarry when she returns. Both stage the impossibility of returning to the old home. Place memory is made out of what we carry away from it, the dust and sand and crumbs stuck in the corners of pockets; it is filled with meaning by the stories that we gather up and pin to it – of gods, ghosts, saints, of rumours, myths and fairytales – and it is only through these that we can take a sense of place with us on a world on the move.

Lawrence, who was raised in the Black Country and now teaches in Birmingham, has a rich record of writing and thinking about local place and how dream, memory, fantasy shape our sense of attachment and dwelling. ‘Quarry’ returns to those themes and works with materials that have fed a wave of new work on landscape and Englishness across the arts in the last decade. Lawrence’s title plays with the idea that writing rests on a heap of resources mined out of common grounds and Eliot’s own practice. In the research process for her novels Eliot kept a series of notebooks filled with extracts from her reading. She copied the final sift of into what she called her Quarry.

Lawrence’s most visible quarried resource in the story is the public information film, The Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water(1973 Central Office of Information dir. Jeff Grant), narrated by Donald Pleasance. At the film’s opening the cowled figure of the Spirit – straight out of the Gothic canons of Matthew Lewis and Anne Radcliffe – stands in a mist-covered swamp. ‘This is the kind of place you’d expect to find me’, trickles out Pleasance’s sickly dark-honey tones. The film then cuts away to an everyday sunlit scene of young boys egging each other on trying to get a ball out of a muddy-banked pit of water: ‘But no-one expects to find me here – it seems too ordinary’. The boy’s foot slips. There’s a splash; then there is silence. It’s a brilliant breaking apart of our conditioning to genres. Death can be seen – just out the corner of your eye – amid the everyday and ordinary places; the real can also be haunted.

Lawrence’s ‘Quarry’ figures that presence of death through the break, the gap, the silences that shape its delicate frame. ‘Bub’ herself takes her new name (the only one we have for her) from the public information film in which we hear that the spirit of the dark waters has ‘no power’ over ‘sensible children’. Bub is safe from death in dark waters, but is still tethered to some dangerous object in its hidden depths, even in the modern day present that the story closes with. The story is an exercise in the painful impossibilities of nostalgia for those whom the past is full of sudden falls, darkness, in which loving violence leaves but a sweet sprinkling of dust to fill the void.

Lawrence’s work claims the right of the ordinary to be, in and of itself, luminous. Her story pushes beyond the wave of new writing, art and music that embraces the aesthetics of the 1970s to look inwards and imagine a ‘deep England’. The late 1960s and 1970s have been mined for their own revivals of English folklore and myth, even as pylons began to stride across the downlands and industrial decline left rust and brickfields on the edges of towns and cities. The aesthetics of public information, mass further education, and life in a provincial town are sampled to present an imagined alternative to the eviscerated municipal commons of now. David Matless and Michael Gardiner have both written recently of the political problematics of this nostalgic return to a landscape of Englishness, even if, as one notable practitioner Jim Jupp suggests, it is an accession of impossibility – a ‘nostalgia for nostalgia’.[2]

Perhaps the best way to grasp the aesthetic of this provincial weird is to skim the catalogue of Ghost Box Records. The label’s house band, Belbury Poly, conjures life in a fictional market town in the borderlands that has an ancient church and recent polytechnic. The design aesthetic of the album covers is inspired by 1970s Open University textbooks. The music, on the other hand, rips open that carefully managed surface of deliberate ordinariness to allow us to hear something like the spirit of dark waters. We’re tuned in to the sounds of another dimension – an alternative modernity that has already split up with our world and gone by on its separate way – thanks to the soundscape of moog and synth and radiophonic experiment that, in themselves, represent near obsolete technological forms.

But despite Lawrence’s early literary interests in magical realism, ‘Quarry’ stays in form as well as in subject in the realm of the everyday. Its concern, as the title suggests, is not with alternative worlds and hauntology, but the stuff under our feet. How we build a world by digging it away and then wonder at its instability. How we exist on a surface, how writing and art forms its own surface, how gaps and sudden falls – elision and caesura, scraped paint and scratched paper – are part of making work. Lawrence’s commitment to realism and the materiality of writing practice in this story is, of course, a fit tribute to Eliot who did more than any other British writer to transform what it was we think a piece of fiction can do in our relationship with the everyday world. It is also, however, a quiet demand for the political significance of a certain sort of storytelling.

In Writing in Society(1983) Raymond Williams looked back over the emergence of the category of ‘regional fiction’ in the twentieth century, a category he saw that was increasingly aligned with ‘working-class fiction’.[3]This sort of labelling, William points out, implies that life in some regions – say London or the home counties – is normal or general, whilst the people and lives anywhere else are, well, regional. Williams’s essay still has much to offer an analysis of the contemporary literary marketplace, which has at least begun to acknowledge the problem of the blithe arrogance of metropolitan, middle-class possession of the ‘normal’.

Williams argues that stories of regional or provincial life remain vital to a state of political self-realization. There is a great need, he argues, for works ‘rooted in region or in class’ which can achieve a ‘close living substance’ from experience:

they seek the substance of those finer-drawn, often occluded, relations and relationships which in their pressures and interventions at once challenge, threaten, change and yet, in the intricacies of history, contribute to the formation of that class or region in self-realization and in struggle, including especially new forms of self-realization and struggle. [238]

Raymond Williams, Writing in Society (1983)

Stories involve a moment of recognition that is in itself a transformation. Forget the late bourgeois idea that novels are concerned with individuals living privately. Williams insists that we make space for fictions – especially in a post-colonial world – that let us see the entanglement of lives, regions, geopolitics and understand the reflexive play of self in that nested scale of society.

Struggle and self-realization is at the heart of Lawrence’s story too. Yet unlike a strong regionalism that we might trace in an arc from Scott, to Emily Bronte, early Hardy and Lawrence, to Benjamin Myers, its landscape is not one of radical alterity. Her work is closer the genre of provincial fiction as it emerged in the nineteenth century with Eliot, Gaskell, Trollope. It is a genre of everydayness and one that became increasingly associated with the middlebrow and the feminine in the twentieth century, perhaps reaching its neutral epitome with Barbara Pym. If its outlines are less extreme, its violence small, its settings middling, the struggle to collective self-realization is no less vital.

Bub’s story is one that many women feel they already know because it’s always been there. The only surprise is that it has come as news to so many: that life is a constant calculation of risk – we could be pinned down by anyone, anywhere at home or out and about – and sensible girls must always look twice before crossing. In Lawrence’s hands that provincial mode is a realization of the self-censorship that so many women practice to stay alive, living carefully in the middle landscape. Try to climb higher, to quarry deep, or stand out, and, like the figure in Goosey Gander, you may find you are flung over the edge, falling.

[1]Denis Cosgrove, ‘Landscapes and Myths, Gods and Humans’ in Barbara Bender ed. Landscape Politics and Perspectives (Oxford: Berg, 1993), pp. 281-305

[2]Michael Gardiner, ‘Brexit and the Aesthetics of Anachronism’, ed. Robert Eaglestone, Brexit and Literature, (London: Routledge, 2018); David Matless, Landscape and Englishness(rev ed. London: Reaktion, 2016);

[3]Raymond Williams, ‘Region and Class in the Novel’ in Writing in Society(London: Verso, 1983), 229-238.

Quarry

A new short story by Anna Lawrence, project writer in residence

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Gav twisted the button on the telly until the picture settled, laid out two sheets of newspaper on the settee and flopped down.

‘Yes!’

Bub looked up from her homework at the dinner table. She limited herself to one wafer biscuit per piece of homework completed, eating it carefully over a plate. She dabbed up the pink crumbs with a wet finger.

‘Not this, Gav, please. Turn it over. What’s on the other side?’

It was that daft advert with Death done up like a hooded monk, stalking round those stupid kids trying to get their ball out of the water. Bub usually pretended she needed a wee when these things came on, and usually never went, peering round the doorframe, holding her breath, watching through her fingers.

It unsettled her; it might make her do something reckless and compulsive, like climbing into an abandoned fridge and shutting the door behind her while playing hide and seek, or trying to catch a firework, or smuggling a rabid dog into the country (although she wasn’t sure when she’d get the opportunity). Mum had taught her how to cross a road, but still, she’d memorised every frame of Tufty the stop-motion squirrel, with his dead black saucer eyes, twitching along the pavement for an ice cream, and when she heard the soft thud, the yelp of brakes when Willy Weasel dashed out behind the van, she always said, ‘Serves him right,’ under her breath. There was something shifty and unwashed about that weasel. But she worried that she, too, would be gripped by the compulsion to run out behind a van, and whenever Auntie Stel gave her coins to get herself a lolly, she refused.

‘I need a wee.’

‘No, you don’t. It’s your favourite.’

‘Adverts are boring. Turn it over.’

‘It’s not an advert. It’s state-funded horror. I am the spirit of dark and lonely water…’ Gav actually rubbed his hands together when these things came on, like a cartoon villain. He saw these stupid films as dares, instructions. Things to try.

“It’s the perfect place for an accident.” He knew all the words and made his voice go deep and creepy.

Auntie Stel had offered to buy her a kite last summer – everyone wanted to buy them things last summer – but she’d said no in case she flew it into a power line. Children who did that – stupid children – deserved to fry like those lardy strips Gav peeled off the wodge of bacon each morning and slapped, sizzling, into the pan. Bub would track what her brother touched with his unwashed hands, and when he’d pulled on his overalls and slammed out, sucking ketchup off his fingers, she crept round the house, wiping raw meat fingerprints from door handles with a bit of Dettol on a hankie. There’d been a film in Biology about microbes. You couldn’t be too careful. Auntie Stel had actually spooned mould out of a jar this morning before spreading damson jam on Bub’s toast. Bub had said thank you and folded the bread into a bit of kitchen paper, saying, with her fingers crossed behind her back, that she’d eat it on the way.

She’d been relieved, at first, to bring her suitcase and her box of books to Auntie Stel’s. In their old house, the absence had pressed on her like great slabs of stone; the place felt hard and hollowed, heavy with a ringing, pressured silence. Auntie Stel’s was full of life. Radio 2 was always chirping in the background. The air thrummed with Woodbine and Glade, the surfaces thronged with porcelain owls in mortar boards and otters smoking pipes and after her shift on Friday nights, Auntie Stel would bring a brick of pink wafers from the factory.

‘Listen!’ Gav cackled. ‘I’ll be back.’

Bub packed away her colouring pencils and her geography book. A letter fluttered out.

‘Shut up, Gav. I hate that stupid Death voice.’

She grabbed the letter and crumpled it up before Gav could see, not that he was watching. She didn’t want permission for the stupid trip anyway. She couldn’t see why the other kids were so excited about a big hole full of rocks. There wouldn’t even be a gift shop, and the coach ride was only ten minutes. She’d dreamed of the quarry after glimpsing it through barbed wire and thicket when Gav took her blackberrying last August, trying to keep her mind off things: the land dropping away, suddenly sheer; the vast sprawling wound of a canyon yawning at the sky; tarry pools and slurry tips and blackened trees and rocks snatched out of earth by machines with claws the size of houses, scraping, crushing, scalping.There was something chilling and thrilling about the scale of it, something alien and removed, like the bleak landscape at the top of the beanstalk. She worried that she would not be able to keep from jumping.

‘Chuck us the biccies, if you’ve left me any, greedy piggy.’ Gav twisted and held his hands out, ready to catch.

‘I’m not chucking it. They’ll go to dust.’ She placed the tin on the coffee table with exaggerated precision. She pushed Gav’s feet off the table. His corderoys were thick with drying mud and the left leg was torn. He levered the lid off the tin and crammed a wafer in his mouth.

‘What happened to you, Gav?’

A thick track of blood all up his shin.

‘Come off in a ditch.’ He spat crumbs. ‘Chain slipped.’

‘I’ll get the TCP.’

‘Don’t bother. Only a graze.’ He picked something off his leg and held it up to inspect it, then wiped it on his t-shirt.

‘It looks like a cut.’

‘Bike’s ok. That’s the main thing.’

‘You need to clean it up.’

‘Nah. It’s just a bit scratched.’

‘You weren’t up the quarry, were you?’ She stood with her hands on her hips, looking down at him.

Every time they argued about the quarry he’d tell her she was daft. It wasn’t just him who went up there, he’d say. He’d seen swimmers, bird watchers, climbers. Some old hippies looking for hornblende to heal their root chakras, whatever they were. Even his old geography teacher scratching at the rocks for fossils.

She’d told him there were chemicals there. What they all called ‘the blue lagoon’ would strip his skin, she said. Dissolve him like a tooth in Coca Cola. He’d said that there were chemicals in the water at the local baths, otherwise they’d all be one big verruca. And what did she think her precious Jif was? Fairy puke?

(Years later, after yet another young man has drowned on a hot afternoon, she wants to ring Gav to tell him she was right and that the Council’s dyed the waters black in warning. But she can’t. The quarry, mourning).

She’d told him how the ground slips. The slopes are too sleep. You can’t get out. The water is too cold, too deep.She’d read about it. She’d seen it on the News. Dead things in there. Livestock. Rusty metal. The bodies of old cars. She’d threatened him with tetanus and drowning, but nothing seemed to work.

‘I said, were you up the quarry again?’ She folded her arms and glared down, trying to be commanding.

He grinned up at her. ‘No, Mum.’

They both reeled, just a fraction, and shock washed through his face. He looked suddenly limp. Bub bit her lip. She wasn’t going to cry. She hadn’t cried since the accident and she wasn’t going to start now. She hadn’t even cried at the funeral. She tried to think of nothing, of the curiously blank limbo of the Play Schoolset, with its soft-lit curved studio walls, the opaque tissue-paper dreaminess of the arched window and the staring rigid blandness of that fat doll, Hamble. She had never liked Hamble.

‘Have it.’ Gav held out a biscuit. ‘Go on. It’s the last one.’ His hands were mottled with dark patches of oil and mud. His fingernails were black.

‘Don’t want it. Your hands are piggin’ filthy.’

‘Have it.’

‘I don’t want anything from you.’

He waved the biscuit in front of her nose. ‘Good clean muck can’t hurt.’

‘Muck’s not clean. That’s the whole point.’

‘You’ll catch something.’

She wanted to tie Gav to a kitchen chair and scrub his whole face with hard green soap until he was all foam; his eyes, his mouth, his ears, his nose. She wanted to smash the Dettol bottle over his head and pour it down his throat. Make him bath in it and burn off the sticky filth on his shin. She wanted him clean and safe. What was it Mum used to threaten?

‘You’ll get botulism.’

‘I’ll give you botulism!’ Gav sprang up and, before she could get away, he’d pinned her to the settee and crushed the biscuit against her mouth. She pressed her lips tight.

‘You’re chicken. Scared of a bit of muck. Just eat the bloody biscuit.’

She shook her head and tried to bat his arms away, but his full weight was on her. He squeezed her nostrils together until she opened her mouth, coughing. He laughed and squashed the wafer in. Oil and muck and sugar on her tongue.

‘I’m not chicken,’ she said, thickly.

‘Suck my thumb. It’s still got crumbs on it.’

She bit him, and he pulled his thumb out, laughing.

‘I’m not chicken, Gav.’

‘What are you then?’

Mum had always said she could trust her to do the sensible thing. Old head on young shoulders. ‘I’m sensible.’

And this is what made her sob, at last, until she couldn’t catch her breath and snot came out in bubbles. Gav put his arm around her. ‘Nah, you’re not chicken. You’re sensibubble.’

And that was what he called her, until ‘sensibubble’ eroded into ‘Bub’ and stuck, as if that had always been her name, and when she remembered the Night of The Pink Wafer, it was Bub who had been there, not the girl she was before.

*

Bub knows to look both ways and to keep looking, but she isn’t quite sure how to becross safely. She is facing her fears. She has driven on the motorway and petted large dogs. She has watched the opening credits of Tom Baker’s Doctor Whoon YouTube without covering her ears and eyes. And now she’s got to ‘Quarries’ on her list. She searches for the quarries she remembers in the books that frightened her – Annerton Pitand Stig of the Dumpand The Yonderley Boy– but can’t find quarries here, just mines and chalk pits and ordinary hills. Her memories slip like grit under her feet. The land slips and crumbles; she is in free-fall, like the old man who wouldn’t say his prayers, goose-flung over the bannister, face contorted in shock and fear. Mum taped up that page in the Ladybird Book of Nursery Rhymes when Bub was little, but then Bub got frightened of Cock Robin, not because it was inherently scary but because it signalled the approach of Goosey Goosey Gander, and then the pages before and after, until she had to hide the whole book under her bed where it lurked and hummed. She finds it in a box in the loft, with Gav’s jacket and Auntie Stel’s owl graduate. She peels off the browned and brittle tape and makes herself stare at the face of the old man, falling. She finds a ranger to take her and says it’s for a project. He points out the artificial osprey nests, the newt habitat, the rewilding, and while he’s not looking, Bub puts her hand into her pocket, pulls out a handful of pink crumbs, and scatters.

Our Map is Released!

Our walking map ‘The Unofficial George Eliot Countryside’ was released in Nuneaton during Heritage Open weekend (Sept 13th-15th 2019). It’s been a joyous thing to work on in collaboration with project artist and designer Paul Smith, writer in residence Anna Lawrence, the George Eliot Fellowship and partners across Nuneaton.

You can download the map as pdf below. The George Eliot Fellowship are distributing papers copies in Nuneaton and North Warwickshire, or you can email ruth.livesey@rhul.ac.uk for copies in the post. Please do add comments on the blog if you take the walk. We’d love to hear about your experiences of it.

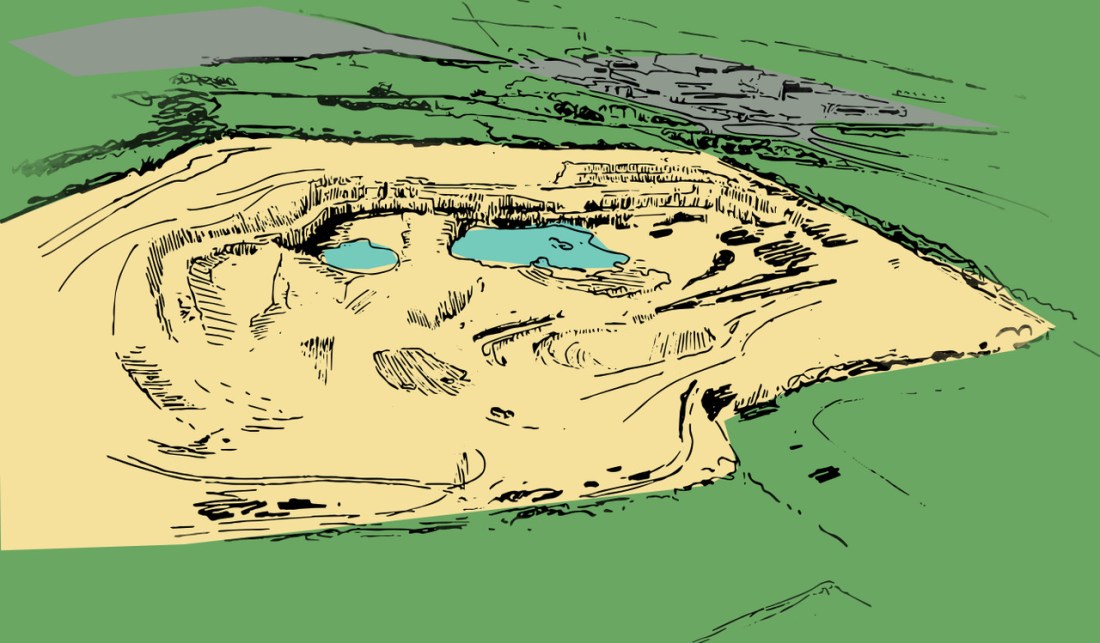

A Postcard from George Eliot Country

We’re pleased to share the first output from the collaboration with project designer Paul Smith (no, not that one). This is our ‘postcard from George Eliot country’ which we’re using for our writing workshops and sharing with project partners across the Midlands. The brief was to produce a postcard that referenced the long history of travel guides to ‘The George Eliot Country’ but to emphasise how that country around Nuneaton in North Warwickshire was in Eliot’s time – and is still now – in a constant process of industrial use and repurposing. Canals, quarries, railways then – underpasses, super sheds, distribution warehouses now: North Warwickshire is beautiful because of its flux and rapid variation. That careful and steady scrutiny of the everyday which Eliot’s works tell us to do can still, on this scale of place, make every feature ‘a piece of our social history in pictorial writing’ (‘Looking Backward’).

Eliot’s writing – such as the opening to Felix Holt (1866), ‘The Natural History of German Life’ (1856), and ‘Looking Backward’ (1879) – reminds readers that to understand landscape we need to see the processes of human labour at work and entangled with nature. It’s all too easy to interpret Eliot’s asides in her fiction about the need to pity those (such as Gwendolen Harleth) without a rooted upbringing in one place as simple regret and nostalgia for rural and provincial town communities; to read her as arguing for an imagined pre-industrial era of small-town Englishness. But Eliot’s work, I’d argue, is clear-eyed in its acceptance that the past is gone and – most of the time – all to the good of those living in the present. In Eliot’s own life story we can see all too vividly that small town and rural communities can stifle as well as support. Mary Ann Evans had to leave home in order to thrive, for all that she built her intellectual life on what she learned in and around Nuneaton and Coventry for three decades.

When we turn to look at the imagery of ‘Eliot Country’ as its been depicted over the past 150 years – the subject of the next exhibition at Nuneaton Museum – there will, I think, be a gap between some of those beautiful sketches and what her writing achieves. The delightful costume dramas of Patty Townsend, for example, give an aura of sweet safety to Eliot’s radically unsteady way of writing pictures which dissolve at the lightest touch to show the hardship behind the picturesque, the shunning that makes community, and a place constantly on the move.

‘Writing with George Eliot at Astley Castle’ Workshop Day

It’s not every day that a 200-year old dead woman sends you a message from the other side. It’s also not every day that you spend the afternoon parading around inside a thirteenth-century castle, or – perhaps most astounding of all – manage to capture and keep the attention of forty twelve-year old children for an entire day when talking about a writer they’ve never read. What more could you ask of a workshop day designed to get children to learn about, interact and engage with their local literary heritage?

The brief for the ‘Writing with George Eliot at Astley Castle’ day was simple. Partnering with the Landmark Trust for one of their Heritage Open Weekends at Astley Castle, we wanted, in a fun and simple way, to educate local students about who George Eliot really was – a.k.a, the local girl Mary Ann Evans from Astley, Nuneaton. We wanted them to be able to picture her as a real person, who sat in the same rooms they were sitting in, and who wrote best-selling novels about the exact places they were seeing with their own eyes. We wanted her to prompt and inspire them to produce creative works of their own. And given the outdoors nature of the day, ideally we wanted all this to happen on a day when it wouldn’t rain – but then again, you can’t always have everything.

So at 10am, on Monday 24th June, nearly forty KS2 students from Croft Junior School dutifully filed into the imposing country church in the village of Astley, Warwickshire. While the students ogled the lofty ceiling and family crests adorning the wall, they were ushered on a whistle-stop romp through Astley’s history by Kasia Howard, Engagement Officer with the Landmark Trust. Then P.I Ruth Livesey stepped in and introduced the woman who was from then on to be the focus of the day, Mary Ann Evans.

Mary Ann, we all heard, was born in Nuneaton, just five minutes up the road from Astley Castle. Her parents were married in this very church, and her father worked on both this estate and the one next door in nearby Arbury Hall. She would have roamed the grounds of the castle just like children would do later that day; would have sat in the same pews as they were currently sitting in inside the church, and she wrote in her novels about the exact views and buildings the children could currently see. It became obvious, for example, after reading about the church in Knebley from Scenes of Clerical Life (1858), that the same church Eliot wrote about seemed suspiciously identical to the very one they were sitting inside. Once in possession of this nugget of knowledge, and armed with the extracts from the Scenes, the students were then accordingly sent on a roaming search of the church building in a quest to tick off all its identifying features. They would later learn that it wasn’t just the buildings of Nuneaton that showed up in George Eliot’s work, but also its inhabitants. One such inhabitant was described by Eliot as the most boring, dull man there ever was, but recognized himself from Eliot’s description and wrote letters to her in complaint!

These and other golden facts were digested in the next part of the day, when the students had the opportunity to not just hear about Mary Ann Evans, but to actually meet her. Cue Eleanor Charman, an actress from local theatre group Sudden Impulse, who was willing to take a shot at adopting for the day the persona of one of the most successful British female authors of all time. Complete with bonnet, book, and strong opinions, Mary Ann greeted some of the students from the village Reading Room, where she was able to further elaborate on the local places – and faces – from her novels. After providing some first-hand suggestions on what to do when getting those indignant letters of complaint from those who recognize themselves in your novels, Mary Ann was left to field questions from the students about her life and writing. Given that she was 200 years old this year – and looking remarkably good for it – we had paid her the homage of providing the students with blackboards and slate pencils to write their questions down on, and the scratching squeak akin to nails on a chalkboard proved an instant source of delight to the students. Despite this, they entered into conversation with Mary Ann with surprising earnestness. ‘Did you ever find your family and their views a little too demanding?’ she was asked. ‘Did you ever miss them or regret your decision to leave?’

Meanwhile, back up at the castle, a raucous scavenger hunt was occurring in the gardens and grounds by a second group of students. Landmark Trust’s Kasia Howard had planted lines and phrases from George Eliot’s sonnets in strategic locations, and after the students had successfully hunted them all out, it was down to them to create a new, personalised remix version of their own.

A third group were upstairs in the castle itself, being led in a creative writing workshop by Anna Lawrence, Writer in Residence for the Provincialism AHRC project, and key figure in the project’s partnership with Writing West Midlands. While the group outside composed their poems and read them aloud, the group inside experimented with prose instead, producing as finished products postcards addressed to George Eliot. These contained descriptions about other local settings dear to them, just like Mary Ann had included in her own novels. When each of the three groups had finished, an immaculately planned changeover would occur and each of them would circulate on to the next activity station. Packed picnic lunches were a pleasant interruption to the grand order of the day, as was the discovery of a dead rabbit, a source of added delight (and horrified squeals) from certain of the students.

It truly was an enjoyable and educational day, and for me, as a young early-career-researcher, it was encouraging to be reminded of how much literature can matter. ‘Impact’ is a word thrown around constantly in humanities academia, but this was the one of the first times I had witnessed the effect that a project like ours could actually have on a real, living, breathing community. Not only were these students learning about a historical and literary figure at Astley, they were also learning lessons of identity. ‘Don’t think that things aren’t important, just because they seem ordinary or everyday,’ the spirit of Mary Ann Evans had been telling them. ‘Even the ordinary and everyday can serve as inspiration to create.’ The feedback we got from the teachers was similarly as edifying. Not only had they themselves been inspired to read George Eliot and visit the other areas she wrote about in her novels, they also all unanimously commented on the positive effect they thought the day had had on the children. ‘They now have a sense of pride in the area they are from, and feel a personal connection to such an important historical figure from their local area,’ said one, and ‘Some of the children really like to write, and George Eliot has been an inspiration to them,’ said another. It was also universally said that they would all be reusing the techniques and resources in their own teaching practice, the exercises having been so successful that one of the helpers of the day commented on the sense of ‘unbridled creativity’ that permeated the atmosphere. It was a result that even Mary Ann Evans herself would have been proud of, and nothing – even a timely shower of rain, just in time for lunch – could take away from the success of it. Her views had originally prompted Mary Ann Evans to leave Astley behind, but that day, her lessons and legacies had most definitely received a homecoming at Astley. And hopefully, with the repetition of these and other related activities, they will continue to live on, right in the very place they began.

With big thanks again to the tireless work and preparation of Ruth Livesey, Kasia Howard and Anna Lawrence; the peerless acting of Eleanor Charman; the invaluable assistance of Colette Ramuz and Natalie Reeve, and the warm co-operation of the Landmark Trust, and all the year 6 pupils and staff from Croft Junior School!

Research Assistant: Tim Moore

Tim Moore is Research Administration Assistant on the ‘Provincialism: Literature and the Cultural Politics of Middleness in Nineteenth-Century Britain’ project. He is a visiting tutor and doctoral researcher at the Department of English, Royal Holloway, University of London. He is due to finish his doctoral thesis on representations of adolescence in nineteenth-century literature in 2021, and is helping co-ordinate project events, seminars, and blog posts.

Project Art and Design: Paul Smith

Paul Smith has extensive experience of delivering high quality map design and art work for environmental charities, local voluntary organisations, and education. Paul will be collaborating on the production of our Unofficial George Eliot Country map in addition to supporting art and design work across our public engagement material.

Paul is also a painter and his works explore place, memory, and the complex nature of post-industrial leisure spaces. You can visit his art portfolio here and see how that body of work enriches our research on this project as we explore colour, landscape, and the problematics of realism. A selection of recent paintings is below.

Project Partner: Writing West Midlands

We are delighted to be working in partnership with Writing West Midlands. From its base in Digbeth, in Birmingham’s creative quarter, this agency is doing outstanding work developing and supporting writers of diverse levels of experience across the region.

The project writer in residence, Anna Lawrence Pietroni, and the PI will be co-designing and leading a short course with WWM at the Birmingham Midlands Institute in autumn 2019. The course draws on project research on George Eliot’s work to develop new writing about place and belonging in the Midlands now. You can register for a place on the course here.

How can our writing communicate a sense of home and belonging or bring to life a place that readers have never seen? This short course will offer writers based in the Midlands the opportunity to craft their skills in evoking settings – whether imagined, remembered, or the everyday. The course draws on the radical example of the nineteenth-century writer, George Eliot (Mary Anne Evans), born two hundred years ago in North Warwickshire, to explore what it means to write in or about the Midlands now. Works by course participants may be featured as part of the George Eliot bicentenary celebrations in 2019, with follow-on opportunities for publication. This course is designed for emerging writers who are looking to develop their work further.

The Unofficial George Eliot Countryside

Since the start of this project in February 2019, Ruth has walked a route around Nuneaton every month. The walk starts from Griff House, up Gipsy Lane, along the canal, across to Bermuda, into the Arbury Hall estate and looping back through industrial estates to Griff – and ending with a large slice of cake at Astley Book Farm after visiting Astley Castle. Taken in the company of the project writer in residence, Anna Lawrence Pietroni, and then the project designer and map-maker, Paul Smith, the result will be a collaborative photo-essay and downloadable map on this site.